Technology and globalization are giving a boost to the trade in fake identity cards

A PACK of photo paper, laminating sheets, spray glue: it sounds like a list of things you need for the school art class. In fact they are ingredients for a fake identity card. Add a dash of Photoshop expertise, and you can earn yourself £1,000 (about $1,500) a week, according to a former vendor, a privately educated British schoolboy, who used to sell fake cards at £25 a time to his classmates.

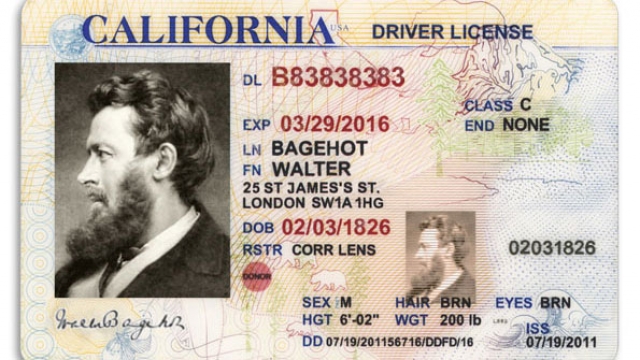

The trade is even more profitable in America. Because the legal drinking age is 21, demand is higher and buyers are richer. An ex-student says he was able to sell bogus IDs for $120 each. Whereas he found holograms and bar codes on American driving licences easy to forge, he failed to copy the magnetic strips. Unwisely, perhaps, some American states are now phasing out licences with magnetic strips in favor of cheaper ones with bar codes.

The business of forged identity cards is booming, particularly in the Anglo sphere. A study in 2009 of American university students found that 17% of freshmen and 32% of seniors owned a false ID. Today the numbers are even higher, experts reckon. Bars near American campuses have started to ask for two kinds of identification.

The use of fake IDs is spreading around the world. China has no great taboo against under-age drinking, so bar owners seldom check. But getting into an internet cafe is more difficult. One well-known place to get a card is the east gate of Rennin University in Beijing. Merchants there report that they can make 100,000 yuan ($16,000) a year.

Fake IDs used to be easy to detect, at least by experts, says Geoff Slagle of the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators. The main problem, he says, were “flash passers”: youths who flash their cards at uninterested barmaids, who do nothing but check the photo on the card.

Yet technology has given the fake ID business a boost. With today’s software and printers, good fakes are easier to make. Counterfeiters no longer need to produce one document at a time; the latest gear allows for mass-production. And since orders can be taken over the internet, the producers no longer need to be close to their customers.

At the same time, IDs themselves have become more sophisticated. This has driven counterfeiters to invest more and raise prices. A decade ago, a good fake card could be bought for between $35 and $50, according to David Myers, an identity-card expert in Florida. Now people have to be prepared to pay ten times more.

As a result, many ID mills have gone online and are now based in China and other Asian countries, where costs are low and forgers hard to prosecute. A popular site is ID Chief. “We are at it again. Here is the Mississippi license,” it touts in its latest offer, which charges $200 for two cards. On August 6th four American senators sent a letter to the Chinese ambassador, asking the country to close down such firms. (Editor’s update: ID Chief has since announced that it would close.)

Western countries could do something about the problem themselves. One improvement would be to introduce a standard national ID card, particularly in America. Not only does each state issue its own driving licence, but there are also numerous other official identity cards. Five years ago Mr Myers counted 542. The figure has since grown, he says.

Fighting technology with technology seems most promising—by replacing ID cards with phones. In Britain a new scheme called Touch2id encodes fingerprints and proof of age on a smart sticker that is to be attached to a mobile. To get served, youths need to swipe their phone over a chip-reader and have their fingerprints scanned.

An overseas counterfeiter would have a hard time to trick such a system, says Edgar Whitley of the London School of Economics. Yet it is also pricey: the Touch2id scanners cost £200 each. Without government mandates or cash to pay for installing such devices, fake IDs are here to stay.